Allan Octavian Hume para niños

Datos para niños Allan Octavian Hume |

||

|---|---|---|

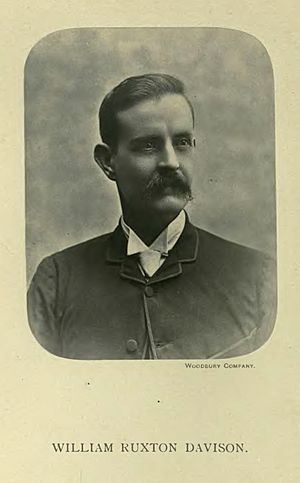

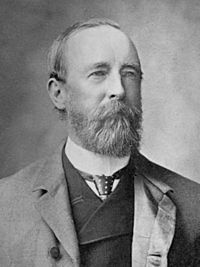

El autor (escaneado de una woodburytipia)

|

||

| Información personal | ||

| Nacimiento | 6 de junio de 1829 Kent |

|

| Fallecimiento | 31 de julio de 1912, 83 años Londres |

|

| Sepultura | Cementerio de Brookwood | |

| Residencia | Inglaterra | |

| Nacionalidad | inglés | |

| Familia | ||

| Padre | Joseph Hume | |

| Cónyuge | Mary Anne Grindall | |

| Educación | ||

| Educado en |

|

|

| Información profesional | ||

| Área | naturalista, botánico, ornitólogo, político, zoólogo, curador | |

| Conocido por | cofundador del Congreso Nacional Indio | |

| Empleador | Indian Civil Service | |

| Abreviatura en botánica | Hume | |

| Abreviatura en zoología | Hume | |

| Partido político | Congreso Nacional Indio | |

| Miembro de | Sociedad Zoológica de Londres | |

| Distinciones |

|

|

| Firma | ||

Allan Octavian Hume (nacido en St. Mary Cray, Kent, el 6 de junio de 1829 y fallecido el 31 de julio de 1912) fue un importante funcionario público en la India Británica. También fue un reformador político, naturalista y ornitólogo.

Es conocido por ser uno de los fundadores del Congreso Nacional Indio. Este fue un partido político que, con el tiempo, se convirtió en un movimiento clave para la independencia de la India. A Hume se le llama a menudo el "padre de la ornitología india" por su gran trabajo en el estudio de las aves.

Contenido

Vida y Carrera de Allan Octavian Hume

Allan Octavian Hume nació en Inglaterra. Su padre, Joseph Hume, era un miembro del parlamento. Allan estudió medicina y cirugía. En 1849, se mudó a la India y un año después comenzó a trabajar en el Servicio Civil en Etawah.

Primeros Años en la India

Mientras trabajaba en Etawah, Hume apoyó mucho la educación. Impulsó la creación de escuelas primarias gratuitas. También ayudó a fundar un periódico local llamado Lokmitra, que significa "El amigo del pueblo". En 1853, se casó con Mary Anne Grindall.

En 1857, Hume tuvo un papel importante durante la Rebelión de los Cipayos, un levantamiento en la India. Por su valentía y acciones, fue reconocido con la distinción de compañero de la Orden del Baño.

Compromiso con la Educación y la Sociedad

Hume creía firmemente que una buena educación podía ayudar a evitar problemas sociales. Por eso, siguió promoviendo la educación de alto nivel. Era una persona muy directa y no dudaba en criticar al gobierno si pensaba que estaba haciendo algo mal.

Criticó la forma en que la administración de Robert Bulwer-Lytton trataba al pueblo indio. Esto le causó algunos problemas con otros funcionarios. En 1879, publicó un libro sobre la mejora de la agricultura en la India, llamado "Reforma agrícola en la India".

A pesar de las dificultades, Hume siguió trabajando hasta 1882. En ese año, dejó el Servicio Civil. Durante todo este tiempo, también dedicó mucho esfuerzo a su gran pasión: la ornitología, el estudio de las aves.

Contribuciones a la Ornitología

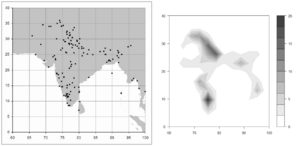

Allan Octavian Hume se dedicó a estudiar de forma organizada las aves del subcontinente indio. Llegó a reunir la colección de aves asiáticas más grande del mundo.

Colección y Publicaciones de Aves

Su primera colección de aves se perdió durante la rebelión de 1857. Pero Hume no se rindió y comenzó de nuevo. Viajó mucho por la India para observar y recolectar aves. Su colección llegó a tener más de 82.000 ejemplares.

Hume publicó varias obras importantes sobre aves. Una de ellas fue "The Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon" (1879-1881), que escribió junto a Charles Henry Tilson Marshall. También publicó "My Scrap book: or rough notes on Indian Oology and ornithology" (1869), su primera gran obra.

En 1872, Hume fundó una revista trimestral llamada Stray Feathers - A journal of ornithology for India and dependencies. En esta revista, publicaba sus nuevos descubrimientos y observaciones. También escribía reseñas de otros trabajos sobre aves. Por su influencia, algunos lo llamaban el "Pope de la ornitología india".

Especies de Aves Descritas

Hume describió muchas especies de aves por primera vez. Algunas de ellas llevan su nombre, como el Búho de Hume (Strix butleri) o la Curruca de Hume (Sylvia curruca althaea). Su trabajo ayudó a conocer mejor la diversidad de aves en la India.

Hume contó con la ayuda de William Ruxton Davison, quien fue el curador de su colección de aves. Davison también realizaba viajes para recolectar especímenes cuando Hume estaba ocupado con sus deberes oficiales.

Red de Colaboradores

Hume creó una gran red de ornitólogos que le enviaban información desde diferentes partes de la India. Más de 200 personas colaboraron con él. Esta red le permitió cubrir una región geográfica muy extensa en su investigación.

Fundación del Congreso Nacional Indio

Después de dejar el Servicio Civil, Hume se dio cuenta de que la gente en la India se sentía desesperanzada. Pensó que era necesario crear una organización para que pudieran expresar sus ideas y preocupaciones de forma pacífica.

La Carta a los Graduados de Calcuta

El 1 de marzo de 1883, Hume escribió una carta abierta a los graduados de la Universidad de Calcuta. En ella, los invitaba a unirse para formar un nuevo movimiento político. Les dijo que si no actuaban por su país, no podrían esperar un mejor gobierno.

Hume creía que si las personas más educadas no luchaban por más libertad y una mejor administración, entonces no merecían un gobierno mejor. Su mensaje era que el sacrificio personal y el desinterés eran claves para la libertad y la felicidad.

Nacimiento del Congreso

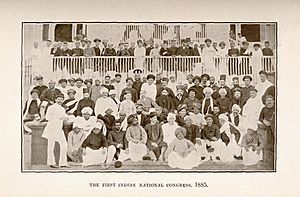

La idea de una unión india tomó forma. En marzo de 1885, se anunció la primera reunión de la Unión Nacional India en Poona. Esta reunión se llevó a cabo en Bombay (actual Mumbai) en diciembre de 1885. Así nació el Congreso Nacional Indio.

Hume intentó que más agricultores, ciudadanos y musulmanes se unieran al Congreso. Sin embargo, esto causó una reacción negativa por parte de las autoridades británicas. Hume se sintió decepcionado cuando el Congreso no apoyó algunas de sus ideas, como aumentar la edad de matrimonio para las niñas indias o enfocarse más en la pobreza.

En 1894, desilusionado por la falta de líderes indios dispuestos a luchar por la independencia, Hume regresó a Gran Bretaña. A pesar de esto, el Congreso Nacional Indio siempre lo recordó con gratitud por su papel como fundador.

Instituto Botánico del Sur de Londres

Después de perder muchos de sus manuscritos ornitológicos, Hume desarrolló un gran interés por la jardinería y la botánica. En 1910, compró un edificio en Londres y lo adaptó para crear un herbario (una colección de plantas secas) y una biblioteca.

Llamó a este lugar el South London Botanical Institute. Este instituto sigue promoviendo el estudio de las plantas hasta el día de hoy. Hume quería que fuera un lugar para aprender y compartir conocimientos sobre botánica.

El instituto tiene un herbario con aproximadamente 100.000 ejemplares de plantas, muchos de ellos recolectados por el propio Hume. También cuenta con una excelente biblioteca que incluía los libros de Hume. Hoy en día, el instituto ofrece clases, tiene un pequeño jardín botánico y organiza charlas y cursos.

Galería de imágenes

Véase también

En inglés: Allan Octavian Hume Facts for Kids

En inglés: Allan Octavian Hume Facts for Kids